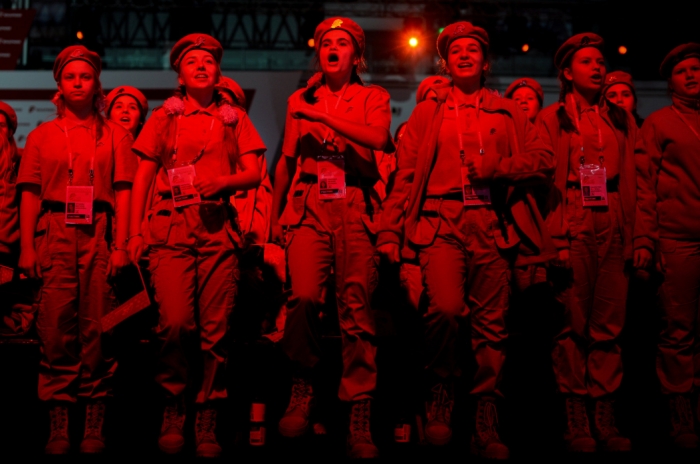

Patriotic Youth Army Takes Russian Kids Back to the Future

KUBINKA, Russia — Often in Russia these days, what is old is new again or, to be more specific, what is Soviet is new again.

The Youth Army, open to both boys and girls, is a militarized throwback to the Young Pioneers of the Soviet era. Meant to instill a sense of Communist zeal, the Pioneers are mostly remembered for their summer camps.

The Youth Army jettisoned the Communist bits, emerging as a kind of hybrid version of the scouts and a reserve officers training program, with an emphasis on patriotism and national service.

The trademark red endured.

If the Pioneers knotted red scarves around their necks, members of the Youth Army sport red berets bearing a pin of the organization’s logo — the red star of the Russian Army superimposed on an eagle’s head.

Formed in May 2016, the Youth Army, or “Yunarmia” in Russian, has grown to include 190,000 children aged 8 to 18 and spread over all 85 regions of Russia.

To mark the holiday in February known as Defender of the Fatherland Day, the Ministry of Defense organized the first national forum of the organization, gathering together around 8,000 members at Patriot Park, the Russian military’s own theme park in Kubinka, some 30 miles west of Moscow.

First, they said it outright. “The Youth Army is cool!” shouted Liza, one of the young women members acting as master of ceremonies.

Second, events started off in the morning with a D.J., who played an amped-up version of old patriotic Russian tunes, adding scratching and other techniques from hip-hop music.

The D.J. was followed by a battery of bubble gum pop bands strutting in outfits like gold lamé miniskirts and belting out tunes at 11 a.m. Some Youth Army members rolled their eyes at the choice of music, and suggested that the army was run by a bunch of potbellied generals who probably thought the kids would find the bands cool.

Third, the event offered access to all kinds of activities that the youths might not get to do otherwise — handling a gun, training dogs, using a 3-D printer and driving a virtual tank.

Sergei K. Shoigu, the defense minister, has been especially vocal about the importance of the organization in creating a bond between Russia’s young and its armed forces. The event came barely a week before Mr. Putin made his own bellicose speech, vowing to restore Russia to superpower status in intercontinental weaponry.

The defense minister was on hand at the forum to offer encouragement, telling the youths that whether they served in the army or went into the performing arts, the main point was to help Russia flourish. Everyone involved seemed to have gotten the memo.

“The idea is to motivate the students to make something new, to implement their ideas, for their future and the future of our country,” said Artur Kuzmin, who was running the 3-D printer.

He was working with a girl and two boys to build a small white plastic robot with a red arm that gave a military salute.

There has been some criticism that the organization is designed to turn the vanguard of the next generation into saluting robots programmed to be hostile toward liberal Western values. One YouTube video has juxtaposed pictures of a Youth Army concert saluting Mr. Putin to 1943 footage from a Hitler Youth rally.

Dmitry Trunenkov, the organization’s leader, rejected the idea that it was excessively militaristic. “These are serious, good-looking young people with fire in their eyes,” said the thickset former Olympic bobsledder, whom the Russians barred from the sport for four years for doping.

“Our movement is absolutely apolitical,” he continued. “The main thing for us is that our country be strong and great, and that, namely, is what we are striving for.”

“Our movement is absolutely apolitical,” he continued. “The main thing for us is that our country be strong and great, and that, namely, is what we are striving for.”

The most crowded events were the sports competitions, the electronic shooting range and the simulated tank driving.

Some members consider the Youth Army their glide path into the regular army. Two teenagers from Ryazan, just southeast of Moscow, said they thought activities like a 12-mile hike through terrain filled with obstacles and exploding devices would give them an advantage when they finally joined the military.

They were not worried about being deployed to conflicts outside Russia, like ones in Ukraine or Syria. Paintings from the Syrian war were featured along one wall.

Aleksei Poltnikov, 17, noted that regular soldiers had been given the option of signing a contract to deploy to Syria or not. “The money there is huge,” he said, adding, though, that it seemed like a quick way to get killed.

“I would not sign such a contract unless my country was under threat,” he said.

Other members conceded that the military videos playing on screens overhead and the recurrent chants of “Russia! Russia!” might convince some impressionable youth that they should go out and fight — no matter who the adversary was.

“The government might be able to use them too easily — that is not a good thing,” said Eldar Kormilin, 17.

Mr. Kormilin and his friends joined the Youth Army because there was little to do in their Moscow neighborhood beyond playing video games, he said. He was hoping to hold a gun later that day for the first time in his life.

“In Russia there are not many opportunities to see a real gun,” he said.

About 10 professionals showed up to offer career advice. Some of it seemed a little odd — if truthful — for young people, like the television correspondent who said that journalists, like military personnel, often end up divorced because they are away from their spouses so often.

Vassily Nesterenko was the painter whose works from Syria were on display. The largest was a tribute to a famous late 19th-century work by Ilya Repin, a reflection on the famous wars of the Russian Empire, called the “Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to Sultan Mehmed IV of the Ottoman Empire.”

Mr. Nesterenko’s version, “A Letter to Russia’s Enemies,” took many of the same characters from the Repin painting but updated their uniforms and put them on a Syrian battlefield.

The Youth Army is also a tribute to the past, a combination of the Komsomol, the youth wing of the Communist Party, as well as the Young Pioneers, Mr. Nesterenko said. “During the Soviet times it was the Pioneers and the Komsomol,” he said, “and now it is a little bit different but the idea is the same.”

Sophia Kishkovsky contributed reporting.

Source: nytimes.com

Countering Military Recruitment

WRI's new booklet, Countering Military Recruitment: Learning the lessons of counter-recruitment campaigns internationally, is out now. The booklet includes examples of campaigning against youth militarisation across different countries with the contribution of grassroot activists.

You can order a paperback version here.