Researching Pop Culture and Militarism: How do things become normal?

Last article, we tried to answer the question of “what is normal?” and after a few examples, eventually settled on “normal is what a group of people are used to.” In this article, we’ll look at an example of the ‘normalization’ process, that is, getting used to something to the point where alternatives are forgotten. We’ll conclude by introducing the main topic of this series: how the presence of the United States military in a surprising amount of aspects of American culture has become so normal that it is no longer noticed or questioned.

“Normal” changes, not just from society to society, but also through time. In a single society, what was considered normal before is not necessarily thought of as normal now, and we can't even begin to imagine what things are normal today that won't be normal in the future. How does that happen? And does something becoming "normal" with time necessarily mean that it is "better"?

The process by which a behavior or belief becomes normal is called "normalization". It is a very popular concept in social sciences, made so by Michel Foucault. In his book Discipline and Punish, he studies how this concept changes over time and the forces that motivated this shift. He entwines normalization with disciplinary power.

"...the primary function of modern disciplinary systems: to correct deviant behavior through discipline through imposing precise norms ("normalization") is quite different from the older system of judicial punishment, which merely judges each action as allowed by the law or not allowed by the law or not allowed by the law and does not say that those judged are 'normal' or 'abnormal'."1

In other words, disciplinary systems (like trials, executions, incarcerations) defined "normal" as what was inside the "norms" or laws, and "abnormal" as what was outside of it. This also implies that, as laws are made by people (individuals or groups), it is these same people that decided what is normal or abnormal. These laws don't have to merely be those contemplated in the legal system; accepting social norms and living by them is living "normally" while challenging them is "abnormal".

We'll take skin tanning in Western culture as an example to illustrate the normalization process. Right now, it is normal to see men and women laying around in beaches, directly under the sun's rays. Coming back to school or work after the summer vacation, telling our schoolmates or coworkers "you're so tan!" is almost always meant as positive remark. There was a time when this was not the case.

In the eighteenth century, upper class women sought lighter skin color by using cosmetics and wearing clothing that covered them up from the sun. "At that time tanned skin connoted humble class origins, as most unskilled workers and farmers would be tanned from protracted sun exposure during the workday."2 Lighter skin, along with their clothing and hairstyles, denoted class and wealth. It meant that they didn't have to work and could spend all day indoors.

During the 1920s, however, this started to change: "As the popularity of leisurely outdoor pursuits such as lawn tennis, swimming, golf and sunbathing brought the bodies of the wealthy outside to play, the pale body began to signify confinement to indoor workplaces and lack of discretionary income."3 Where before, being pale meant you had enough money not to work and spend all day indoors, now what showed off your wealth was spending time out of doors. Sunbathing, swimming, and other activities wouldn't be possible if you had to be working inside at a factory. The tan became a sign that you were wealthy enough to have a lot of leisure time.

This trend was made official by "...Coco Chanel's famous pronouncement, 'The 1929 girl must be tanned. A golden tan is the index of chic!'..."4. Bikinis and the Southern California lifestyle began to become popular, and "...it was not long before Hollywood stars and fashion bodies began to show off their bronzed bodies and rave about their tans.."5. The tanning bed became a product around this time.

Do societies move forward? Is all change, progress? Is what is normal now necessarily better than what was better before? The mere idea of “society moving forward” (or evolving) is a very problematic subject. The social sciences spent their first hundred years with this idea that societies in the present were necessarily better than societies in the past, and that the Western society was the best and most advanced society, representing the present and future (modern) of civilization, while other cultures and societies were less advanced, therefore primitive or stuck in the past. This notion was heavily debated and the notion of Social Evolutionism eventually dethroned. Now social theory mostly asserts that societies are relative to each other, neither one better or worse, just a result of their own history and conditions.

Likewise, the past is not necessarily better or worse than the present; while some ideas and practices that are harmful to people are forgotten and replaced, new ones can crop up and take their place. We can see this with society’s changing attitude: as tans, artificial and natural, became popular, medical authorities like the American Medical Association, American Association of Dermatology, American Cancer Society, Skin Cancer Foundation, National Cancer Institute, the Federal Trade Commission's, Food and Drug Administration, Centers of Disease Control and Prevention claim that tanning can cause cancer, particularly when done through tanning beds.6 Despite being a relatively recent development (unlike other known carcinogens like tobacco), the practice of skin tanning wasn’t hampered by these findings: “In the contemporary United States, tanned white skin may connote that its possessor is a healthy, relatively affluent, sociable, physically fit, and attractive person…”.7

In the normalization of skin tanning, we can see two aspects of the process:

- One of aspect of society changing can affect the whole. In this case, most of the labor force moved from toiling in the fields to doing so inside factories, changing how tanned, white skin was regarded.

- Celebrities, popular, and powerful people have powerful influence in mirroring, setting, and deciding new norms, often to their own benefit. Coco Chanel only got tanned accidentally when on board a Mediterranean cruise, yet, through her fame as a fashion icon, she managed to turn the accident into a trend that has outlived her.

The normalization process has happened an infinitude of times throughout our history. Times changed, though not by chance, or on their own; the events that shape history are many, and incredibly varied. It would be a mistake to think of the tide of history as part of nature, uncontrollable and inevitable. That would mean ignoring the very real effects of people in history and in their society, as well as the equally real presence of individuals and groups who manipulate and normalize certain conducts for their own benefit.

Keeping that in mind, we can start talking about militarism. Previously, we referred to it as “how the presence of the military in many aspects of our culture has become normal”. This presence does not merely mean the uniformed soldiers, but also includes values, ideals, aesthetics, and just the general sense that having a strong military power is not just necessary, but the best policy for a nation. Militarization is the effort to build up a military force, whether through arms or people.

It is NNOMY’s belief (substantiated by copious evidence) that militarism in both the United States and Western culture at large and its emphasis on martial values is not coincidental; it is in the interests of some that this is so. Even beyond those interests, militarism is pervasively embedded in Western pop culture, its presence largely unexamined by the casual consumer.

In the next installment, we will give talk more in depth about the definition of militarism, as well as talk about Japanese militarism, and how it was shaped by a wide variety of forces before World War II.

To read more on the history of tanning:

http://www.skincancer.org/prevention/tanning/tale-of-tanning

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2012/feb/19/history-of-tanning

References

1 Gutting, Gary, "Michel Foucault", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/foucault/>.

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7: Vannini, P. and McCright, A. M. (2004), To Die For: The Semiotic Seductive Power of the Tanned Body. Symbolic Interaction, 27: 309–332. doi:10.1525/si.2004.27.3.309

Series Homepage at http://nnomy.org/index.php/en/resources/blog/researching-militarism-selene-rivas

Selene Rivas is an anthropology student at the Central University of Venezuela and an intern for the National Network Opposing the Militarization of Youth. Contact her at srivas@nnomy.org

###

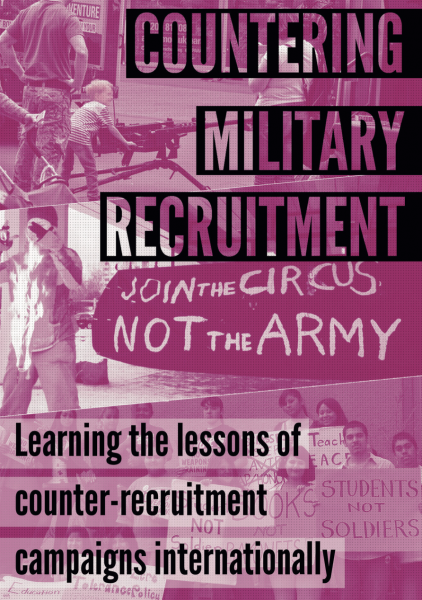

Countering Military Recruitment

WRI's new booklet, Countering Military Recruitment: Learning the lessons of counter-recruitment campaigns internationally, is out now. The booklet includes examples of campaigning against youth militarisation across different countries with the contribution of grassroot activists.

You can order a paperback version here.