Football, the military and one Florida high school student’s difficult choice

By Kent Babb -

MONTICELLO, Fla. — The binder sat open on his adoptive mother’s lap, turned to the page where the scholarship papers lay in a transparent sleeve.

Nik Branham said nothing, holding the phone in its camouflage case close enough that his face glowed. The woman supported her 17-year-old’s plan to join the Army, but she didn’t understand it. These papers were a miracle, as she saw it, college at least partially paid for because of the hell he had survived, a chance at an education and maybe a few more years of football, the game he once loved.

“I done explained everything,” said Alice Branham, a foster parent who adopted Nik and his older sister Ambrosia six years ago, and when the process was complete the state of Florida offered the “Road to Independence” scholarship. In the time since, Alice had come to love him, to become inspired by his confidence and also frustrated by it, to refer to him as a “pit bull”: Once he sank his teeth into a decision, he wouldn’t let go.

“Nobody can change my mind,” he said, and Alice looked away.

In the South, like most parts of the United States, football and the military are cultural siblings — two powerful and venerable forces, brought together week after week for the crowds and cameras. There are anthems and flyovers, shared terminology like “formations” and “blitzes,” pride in home teams and service branches passed through the generations like precious heirlooms.

But beyond the bright lights and choreography, these grand American institutions face frequent and, often shared, criticism: that both are overgrown and unnecessarily powerful, that players and soldiers are trained for games and combat but rarely are prepared for a return to normal life, that football and military recruiters sell a glamorized version of reality — rarely mentioning the shared risks of long-term brain injuries, psychological disorders and a shortage of post-career support.

In Jefferson County, this mostly rural and increasingly poor area in the Florida Panhandle, young people are drawn to the glory, sure, but many of them see football and military service as something more fundamental: a way out. Indeed, surveys have shown Jefferson County — nearly 19 percent of the roughly 14,200 residents here live below the poverty line — as a high per-capita producer of both college football talent and military recruits. An audit of 2013 college football rosters by Mode Analytics found that about one in every 83 boys left the county to suit up for a college team. “We’re definitely a tougher breed,” said DeVondrick Nealy, a Monticello native who’s now an Iowa State running back.

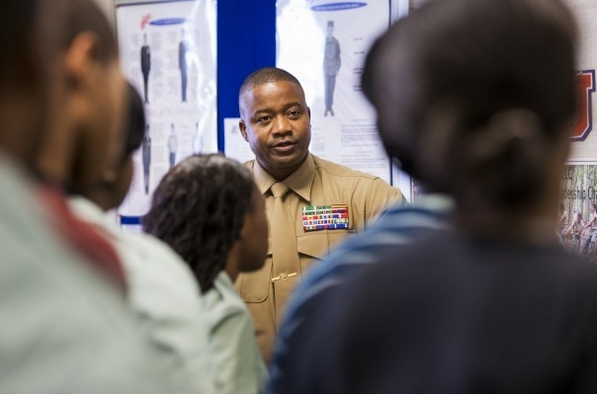

Nikolas Branham, an Army signee and the commander of the JROTC program has a friendly arm-wrestling match during lunch with Tyrone Thompson,

a math coach at Jefferson County Middle/High School. (COLIN HACKLEY/For The Washington Post)

Data supplied by the Department of Defense shows Florida as the nation’s second-leading per-capita producer of military personnel, behind only Georgia, and though the Pentagon does not maintain county-by-county data, a 2007 study by the nonprofit National Priorities Project revealed Jefferson County as one of the state’s most fertile recruiting grounds. Perhaps more telling, Jefferson County Middle/High School educates about 200 high school students; more than 85 percent participate in the Army Junior Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. “For these young people, it represents hope,” said Kent Watson, one of the school’s JROTC advisers.

Alice Branham has heard it before, trying in her own mind to measure the opportunities against the downsides. She used to bring them up with Nik, pointing at the pictures of the football players in the college brochures, trying to stoke another kind of fire. But Nik has not wavered. He had his reasons, and the molten ideas of a teenaged mind hardened and turned to stone.

So now Alice doesn’t bother. She just sits there in a dark room, her hand resting on that paper with “scholarship” typed on it.

“Nobody understands,” Nik said. “It’s a place I can belong.”

They went for ice cream that first week, gathering later in Alice Branham’s den. It was February 2006, her fourth year as a foster parent. By then she had learned children were more talkative after eating dessert, and it was important for her to get to know them.

She listened as some shared their memories; waited as others struggled to trust. She spent one night holding a girl as the child lay silently in her new home, trembling in her sleep. This time, the boy was talkative and the girl was reserved.

Alice began with an easy question: Do you know when your birthday is? Then, something more complicated: What do you want to be when you grow up?

It made Nik Graham smile, maybe for the first time since walking through Alice’s door as little more than a number, her 34th foster child, and the subject of a short biography she slid into a clear sleeve and snapped into an empty binder.

Nik, who was 8 at the time, told her he wanted to be a police officer. Not a doctor or a football player? No, he said: a police officer. But why? He wanted to arrest his biological family, the only way to separate them from drugs.

Slowly, the boy’s story trickled out. He had been 5 years old when the strangers came, his siblings’ shouts — “They’re coming! They’re coming!” — piercing the night. He hid in the top of a closet, but the social workers spotted Nik’s dangling foot, exposing his eight brothers and sisters, another night their biological mother had left them alone.

They disappeared into foster care and group homes, the family split and sent to different places. Nik and Ambrosia Graham stayed together, bouncing here to there, home to home, and now here they were. He said he is uncertain who his biological father is and uninterested in knowing him, and he has resisted his biological mother’s attempts to reconnect. “I always felt like I was abandoned,” Nik would say years later. “I don’t feel like I fit in anywhere.”

In those early years, he was afraid of the dark, of heights, of being alone. When someone pointed a camera at him, he raised his middle finger. When someone told him he was loved, he couldn’t believe it. “He came in here broken,” Alice recalled.

She pointed him toward a local football team, where he played quarterback and, like so many of his neighbors, he dreamed of playing in college or even the NFL. They joined a church. They participated in community activities. Nik excelled, his confidence growing, and Alice pushed certificates and newspaper articles into that binder, its spine growing muscular with achievements. He found trouble only when he wanted to feel the pleasant sting of discipline, turning his bedroom television on one night just loud enough for Alice to hear it, storm in and remind him that she cared.

Alice stood at the sink the night Nik walked in and asked if she could adopt them. The question was surprising, but the way he asked it melted her. “When I look in the face of that boy, who has been through hell and back, how can I not try?” she said. “I think to myself: I can make this better.”

The process took a year, but the state awarded her custody of Nik and Ambrosia, and soon their last name was changed from Graham to Branham. Nik’s past was disappearing, a turbulent life dissolving in place of stability and a chaotic childhood forming a base for a promising future.

Soon after they arrived home as a family, Alice held the scholarship form the state of Florida offered for adopted children to eventually continue their education and pursue independence. Then she opened the thick binder, sliding the paper into a sleeve before mashing the folder closed.

Two years ago, a retired Army sergeant first class set up a table in the school cafeteria, spreading literature across the surface and setting two chairs on opposite sides.

Terry Walker had spent his final 16 enlisted years in the Tallahassee recruiting station, making frequent drives to Jefferson County, which like other rural counties in the Panhandle he saw as a recruiting “hotbed.” Now, the Jefferson County school district was asking him to engage youngsters in a different way: by transforming the high school’s JROTC program.

One by one, the kids sat in front of Walker, collected their brochures and ballpoint pens, and he turned on the old sales pitch. “Where do you see yourself in five years?” he began like always, eventually offering a kind of Army Lite to the kids: structure and discipline (for one school period per day), a chance to lead (early “signees” would be named officers), and opportunities for travel (cadets with at least a 2.5 grade-point average would be treated to an annual, three-day reward trip in a different part of Florida). “That,” Walker said, “was like heaven to them.”

Walker inherited a 10-cadet corps, and after four weeks he was instructing 65, and a year later there were 120 students wearing green. This year, Walker said, more than 170 students are in the JROTC, the program so popular that the school ran out of uniforms.

Nik was among the first to join two years ago, reiterating to Walker his goal of becoming a police officer, and almost immediately, feeling the draw of regimentation and strictness. He came home one day to tell Alice that he had put on hold his plan of joining a police force; now he wanted to be a military police officer.

“I thought about the big picture,” said Nik, who now holds the corps’ highest student post as battalion commander.

Walker, who’s also the school’s athletic director, perhaps did not. For all the common ground occupied by football and the military, an overlooked fact is that their interests don’t always harmonize. Fifty-one years after Navy quarterback Roger Staubach won the Heisman Trophy, the most recent time a service academy player won college football’s most prestigious individual award, today’s elite prospects rarely consider playing for Army, Navy or Air Force, whose academic standards and requirement that players enter active duty have turned away many top players.

In Jefferson County, the rise of the JROTC has coincided with the decline of its once-prominent football program — though school officials insisted it was merely a coincidence. After winning its sixth state championship in 2011, pushing the small school into a tie with the big-city football factories for most titles in Florida history, Aaron Sheppard is the Tigers’ third football coach in four years. Sheppard said the program receives zero dollars in public money, and many of the county’s best players have made a habit of transferring to other high schools, often in search of more modern amenities. “We really inherited a mess here,” Sheppard said, standing in the school’s dilapidated weight room.

The JROTC receives more than $7,000 in annual government assistance, Walker said, enough to pay for charter buses, hotel rooms and crisp uniforms — differences young people like Nik, a football team captain this past season, have come to notice. Although Nik’s college football prospects likely begin and end with a walk-on role at a small college, Sheppard seemed nonplussed that Nik had no desire to pursue even a faint chance at playing the college game. The coach said another player on next year’s roster, a potential national recruit, is also considering forfeiting a college football career to join the military. “I’ve never heard that,” said Sheppard, a newcomer to Jefferson County. “I would take football. But I love football.”

The coach insisted that, in Monticello, the game’s influence might have temporarily ebbed, but it remains king. Walker, who hired Sheppard, pondered his coach’s words and shook his head.

“They’re not the king now,” Walker said, “because they’re losing. Right now that made us the king.”

Nik sat at a desk one Monday afternoon in the school’s JROTC office, dozens of camouflage fatigues and dress green uniforms hanging behind him, boxes packed with spare helmets and shelves lined with rank patches.

He typed in a Web address, and when the page loaded, he pecked names into a search box. He clicked the mouse, and a jailhouse mug shot appeared. The man in the picture was an uncle, Nik said, and too many of the man’s years had been lost inside a prison cell.

Click. There was his great-grandfather, who spent his final two decades inside a cell before, Nik said, the man died in prison last year.

Click. Another uncle, this one with the high cheekbones that, Nik said his relatives have told him, look so much like his own. Nik was supposed to be just like this uncle when he grew up. “We basically look the same,” the young man said. “It was going to be me.”

Football and military service offer Monticello’s young people two pathways, but there is a third: a long and winding highway that, after a left turn, ends at the Jefferson Correctional Institute. The state prison houses more than 1,100 inmates, but with a 209-member staff, it’s also the county’s largest employer; most everyone in town knows someone who has spent time, either voluntary or not, inside those walls.

Nik said he knows little about his biological mother, other than that she spent time in jail, or the specific reasons why his siblings were removed from her home. On certain days when he gathers the nerve, he types another name into the search box and stares at the face of the man he believes to be his father. “Certain people,” Nik said, “you don’t consider family.”

Other relatives call him sometimes, questioning why he’s set on joining the Army. Why is he so determined to leave Jefferson County? Why does he wear those camouflage pants all the time, carry that camouflage phone case? Why, of all things, does he want to become a police officer — hardly seen in some circles as a noble vocation. “ ‘Why are you always being different?’ ” he said they ask him. “Because I want to be different.”

Others ask more nuanced questions. Alice has reminded him of the opportunities elsewhere and the threats she now finds impossible to ignore. Nik might not pay attention to the news, but she does. She hears about the casualties, watches footage of flag-draped caskets, reads stories about some soldiers who come home and are never the same. She no longer gets upset when Nik tunes her out. “He ain’t got nothing but guts,” Alice said.

Nik became a youth minister at age 16, was in the homecoming court and did back-flips in drill practices and parades. If he has decided on military service, wouldn’t such a bright and charismatic soul be better served to attend college first, complete his degree, then apply to Officer Candidate School? Even Walker, the JROTC leader, said he plans to discuss Nik’s options with him.

But it won’t matter, Nik said. His decision is made. The other paths — football injuries and college GPA requirements and homesickness — are too uncertain; it is far too easy to turn around.

The way Nik sees it, there is only one way to eliminate the possibility of ever being in a picture like the ones on the computer screen, to never find himself tempted to cut corners to support himself or Alice, of knowing he will never disappoint his own future children the way he was once disappointed. That is by signing a contract and, when he turns 18 next August, going wherever the Army tells him to go. “It’s a guarantee: I don’t have to worry,” said Nik, who plans to pursue a college degree after he is discharged. “I won’t ever be in that cycle.”

He clicked the browser window closed, and the mug shots disappeared. He stood and headed toward the afternoon’s drill practice. “It’s going to be hard,” he said. “But nothing in life is easy.”

Source - Washington Post

###

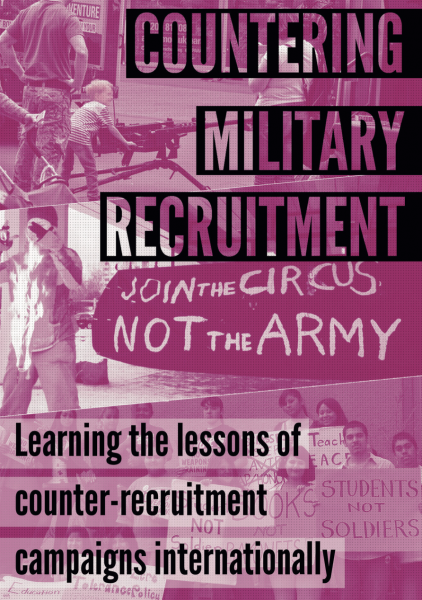

Countering Military Recruitment

WRI's new booklet, Countering Military Recruitment: Learning the lessons of counter-recruitment campaigns internationally, is out now. The booklet includes examples of campaigning against youth militarisation across different countries with the contribution of grassroot activists.

You can order a paperback version here.